Lekh Lekho and Unfair trials / לך־לך און אומיושרדיקע נסיונות

We are morally obligated to do more than just "be kind".

This is a weekly series of frum, trans, anarchist parsha dvarim [commentaries]. It's crucial in these times that we resist the narrative that Zionism owns (or worse: is) Judaism. Our texts are rich—sometimes opaque, but absolutely teeming with wisdom and fierce debate. It's the work of each generation to extricate meaning from our cultural and religious inheritance. I aim to offer comment which is both true to the source material (i.e. doesn't invert or invent meaning to make it say what I want it to say) and uses Torah like a light to reflect on our modern times.

As leftists,

the presidential election this week brings us disappointment, but we can't let it fester into despair. There is too much work to do.

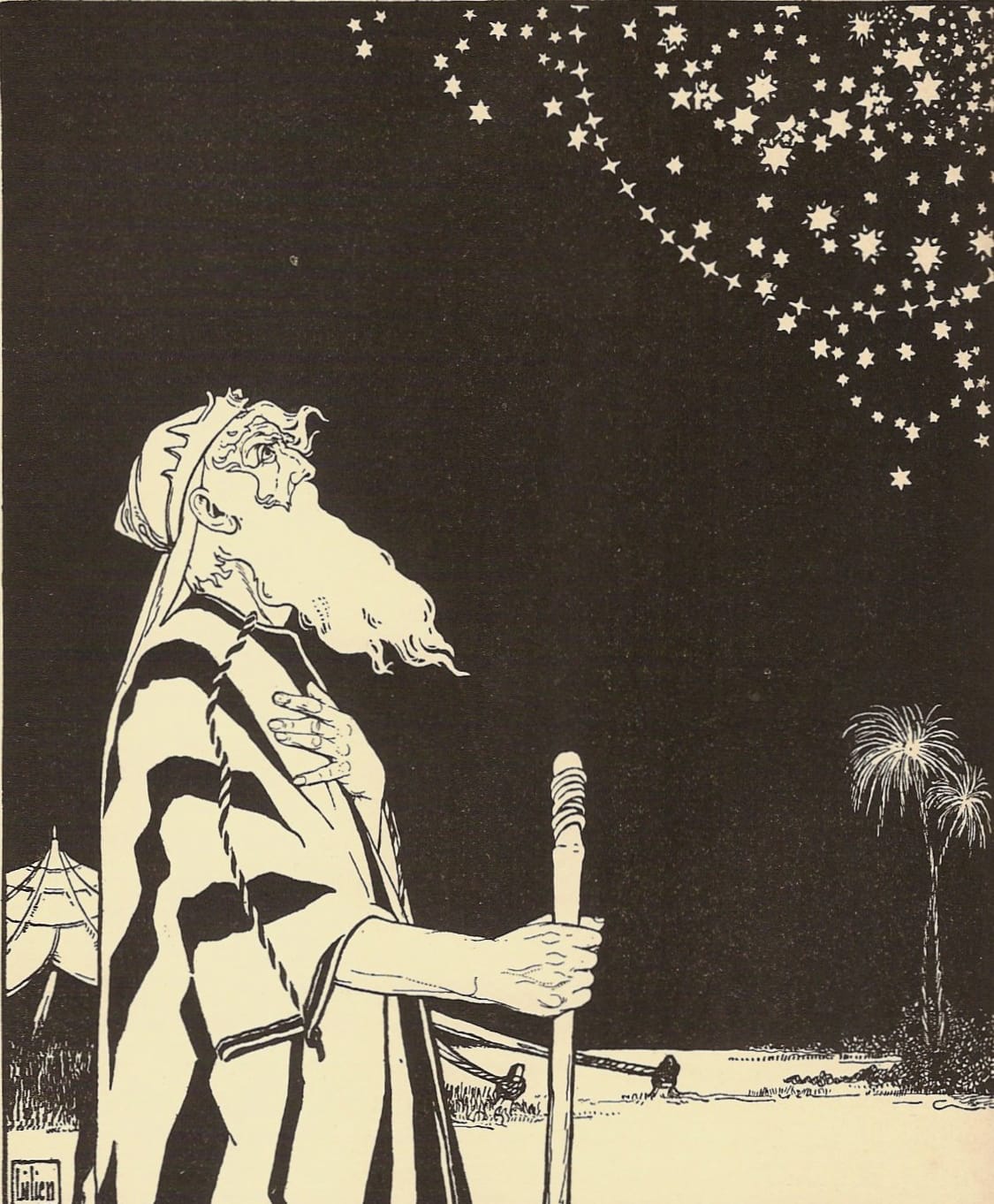

The parsha this week is once again dense with narrative: Avrom, the first Jew, is a wife guy; Lot travels to Sodom and becomes a prisoner of war; we get several divine name changes; themes of infertility, parenthood, and ancestry; the complex relationships between Soray and her servant/metamour Hogor and their children, half-brothers Yitskhok and Yishmoel, widely understood to be patriarchs of the Jews and the Muslims respectively. This is a parsha full of blessings and curses, of battles and spoils, of very personal human struggles, hints of sodomy (subtext) and self-circumcision (text). There's a lot here for trans and ger [convert] readings. We could talk about polyamory, or the ways that Torah and medreshim are used to assert Jewish supremacy and support the genocide. I could spend the whole dvar dissecting one of my favorite lines in Torah, an existential promise by Hashem to make the Jews like the dust of the earth.

But this week, given the news, I'm most interested in Avrom and Soray's journey from their home in Kharon to Knoan, Mitsrayim, and the holy land as a parable of spiritual growth and empowerment in difficult times.

"Get yourself out"

Bereshis 12:1

Hashem tells Soray and Avrom and Soray to leave Kharon at the ages of 65 and 75. This must have been uncomfortable. We too are being asked to do things that are uncomfortable. None of us should be fighting fascism, struggling to have our basic needs met, watching our loved ones carry the increasingly unbearable burdens of rent, debt, medical neglect, bigotry, police brutality, rising food prices, climate disasters, and the criminalization of anyone who dares to protest these conditions. It's deeply unfair and I hope you give yourself the grace to cry about it.

To be alive today means is to inherit a moral obligation to make the world better. Most people are content to limit the scope of their influence to "being kind" rather than meaningfully address systemic violence: these small actions have merit, especially in times like this. But for those of us who can't live with ourselves if we don't step up and try—really try, pushing through our own discomfort and potentially taking on genuine risks—not just to be good but to fix things, being kind isn't good enough.

This is the end of the public preview. Sign up for $5 a month to read the full dvar and support trans antizionist Tōrah scholarship.

Money shouldn't a barrier to accessing writing, art, and culture. If $5 a month isn't sustainable for you, please email me and I'll send you the link to sign up for free.