Mikets / מקץ

This is a weekly series of frum, trans, anarchist parsha dvarim [commentaries]. It's crucial in these times that we resist the narrative that Zionism owns or, worse, is Judaism. Our texts are rich—sometimes opaque, but absolutely teeming with wisdom and fierce debate. It's the work of each generation to extricate meaning from our cultural and religious inheritance. I aim to offer comment which is true to the source material (i.e. doesn't invert or invent meaning to make it more comfortable for us) and uses Torah like a light to reflect on our modern times.

Content note: Discussion of food and starvation in Gaza

Bereshis 41:1–7

I can't do normal Torah study right now.

Paro's (Pharoh's) dreams are still coming true, collapsing and flattening time: the seven good years and bad years are both happening right now. There is a disturbing contrast between my life in New York City, walking through the beautiful December fog and spending the week in Yiddish New York, celebrating and fully participating in my ancestral culture; and the lives of my Palestinian friends, barely surviving in the IDP camp in Nuseirat, living in tents unfit for rain or winter, cold and starving through a genocide. One of them is a 14 year old girl, Areej, who has the flu and no access to medicine. Her uncle, Kamal, has ear problems now because of the bombing so nearby. My friend Madaleen's mother, Manal, frantically calls me 20 times a day because she doesn't know what else to do. We are living in Paro's dream. I am having nightmares.

If I must comment on the parsha, the only part that feels possible—the only part that lets me be grounded in some righteous anger rather than swimming in endless despair and intergenerational trauma-empathy—the only moment that I can latch onto is the psuk on the place settings for the meal Yosef hosts for his brothers.

Bereshis 43:32

Yosef has gone from slave to prisoner to second-in-command of Mitsraim ("the narrow place"; often translated as "Egypt", doing us all a disservice). There is famine across the world but because Yosef accurately interpreted Paro's dreams, Mitsraim is prepared. Yosef's brothers in Knaan are starving and come to Mitsraim to beg for food; they don't recognize Yosef, who they sold into slavery decades prior. Yosef hosts them for a meal.

The table is set: Yosef sits by himself, his brothers sit by themselves, and the Mitsraim sit by themselves. Chizkuni says Mitsraim "detested eating at the same table as aliens, as they felt that they were a superior race and everyone else was way inferior"; Rashbam agrees that the Mitsrim are haughty. Radak says that they sat separately because the Hebrews ate meat and the Mitsraim only reared animals for wool and milk, and to eat them was abhorrent, and that Yosef sits alone to mark his exalted position. Sforno says that Yosef sits alone so that his brothers won't recognize him as a Hebrew, but he also doesn't sit with the Mitsraim because he isn't one of them.

There is little more we can do to connect with our neighbors than breaking bread. Refusing to sit with each other to eat is more than a marker of status; it's a social separation that prevents building meaningful relationships with each other. Maybe social status and separation is the same thing.

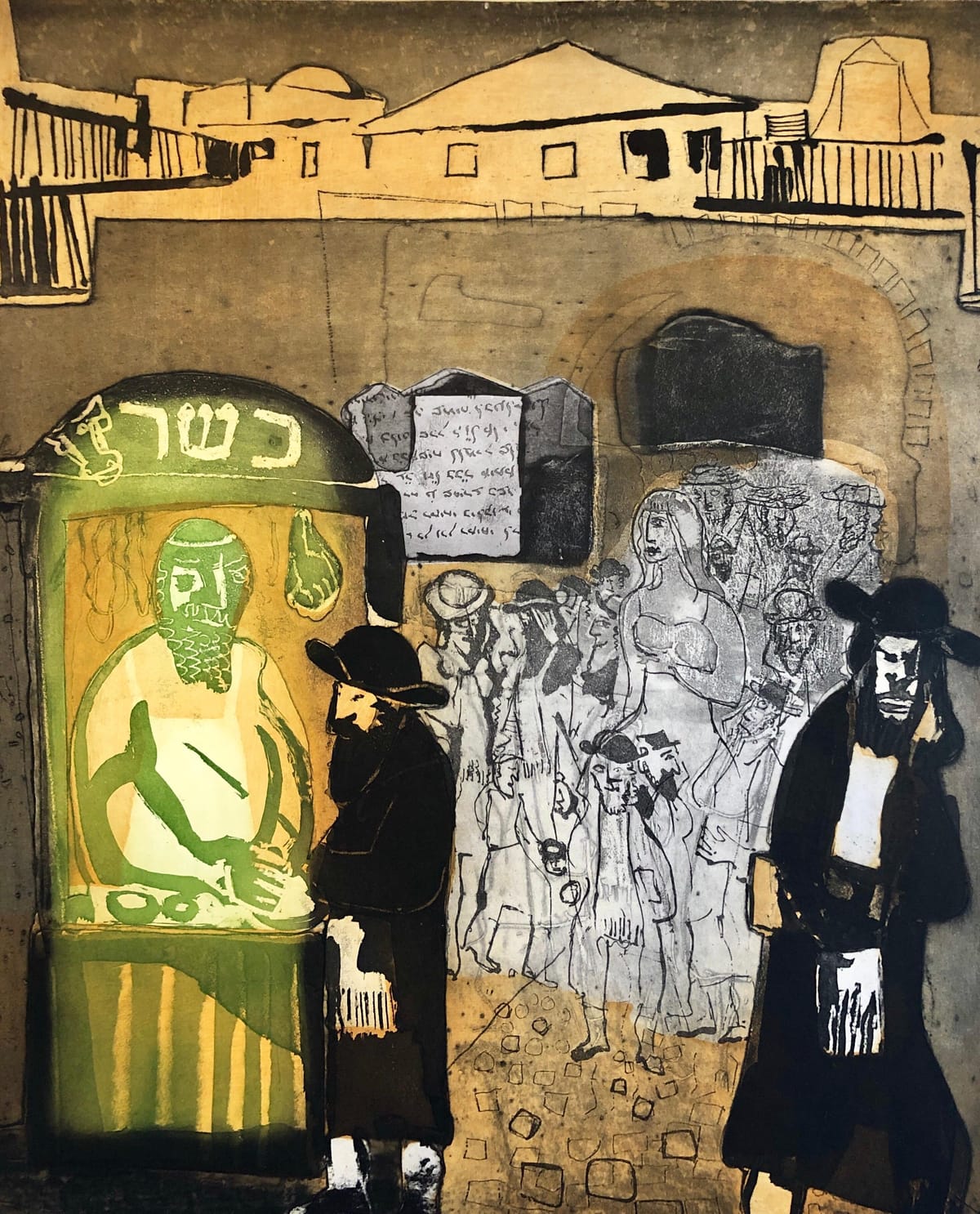

I keep kashrus (kosher) and am struggling to justify why. I'm angry that this observance precludes us from eating with people who don't also keep kashrus. It goes beyond being a preventative commandment against assimilation; it is a mark of distrust, that goyim (and Jews who aren't shomer kashrus) don't know—and would never care to learn—how to prepare food in a way that is acceptable/accessible for us. There are all kinds of politics involved in whose kashrus we trust, further separating us not only from our wider, external community, but our internal frum communities.

The parsha portrays the Mitsraim as disdainful because they won't eat with the Hebrews; our kashrus norms make us disdainful. We can invite goyim and non- shomer kashrus Jews to eat at our tables, but they can't host us. Their food isn't good enough for us. It's insulting.

I am not a halakhik expert, but it seems there is a gulf between what Torah commands and what we practice as modern Jews. We are making our lives needlessly difficult, which on its own would be fine. The difficulty of observant Judaism is something I cherish. But we are also erecting very real barriers to connecting with other people. Our collective anxiety about losing our cultural identity—simply by eating with other people—betrays how little faith we have in ourselves and in Jewish continuity.

Talk about food and famine is not abstract; my friends in Gaza are still starving. What a luxury that I can sit here and complain about what I eat, the way I eat, and how my community expects me to eat alone instead of worrying about where to get my next meal. This Jewish isolation is self-imposed. I know I ask often—but my friends in Nuseirat text me often. I ask how they are and the answers are more than sufficient to move to me to action. If you are living comfortably right now, please donate generously and courageously to my friend Manal so that her and her family can survive with a hope to see an end to this war. If you are not quite living comfortably, but you are not food insecure, please consider donating the cost of a meal to them. Most of us are insulated from the devastating effects of war, but this is a not a normal time, and it is certainly not a time of abundance. It is a time to ration what we have—to help each other—so that we can all live to see the other side. Let's act accordingly.