Vayetsey and Hunger / ויצא און הונגער

The forsaken—the hungry—are not bound to the same obligations as those with bread, clothes, and peace

This is a weekly series of frum, trans, anarchist parsha dvarim [commentaries]. It's crucial in these times that we resist the narrative that Zionism owns or, worse, is Judaism. Our texts are rich—sometimes opaque, but absolutely teeming with wisdom and fierce debate. It's the work of each generation to extricate meaning from our cultural and religious inheritance. I aim to offer comment which is true to the source material (i.e. doesn't invert or invent meaning to make it more comfortable for us) and uses Torah like a light to reflect on our modern times.

Content note: Discussion of starvation in Gaza; and poverty and hunger and more generally.

Before we start, an appeal: I'm still raising money for my young friend Areej. She's living in an IDP camp in Nuseirat, Gaza with her mother and four siblings. So far, with your generous help, I've sent her $340 to help them buy food. Today בס"ד I also raised $1,000 that was sent to another family living in the IDP camp. My immediate network is tapped for money right now, but if you have anything further to give, please donate. It will make a huge material difference to Areej and her family as they struggle to survive.

וְשַׁבְתִּי בְשָׁלוֹם אֶל־בֵּית אָבִי וְהָיָה יְהֹוָה לִי לֵאלֹהִים׃

so that I come back to my father’s house in peace, then Hashem shall be my God:

Bereshis 28:20–21

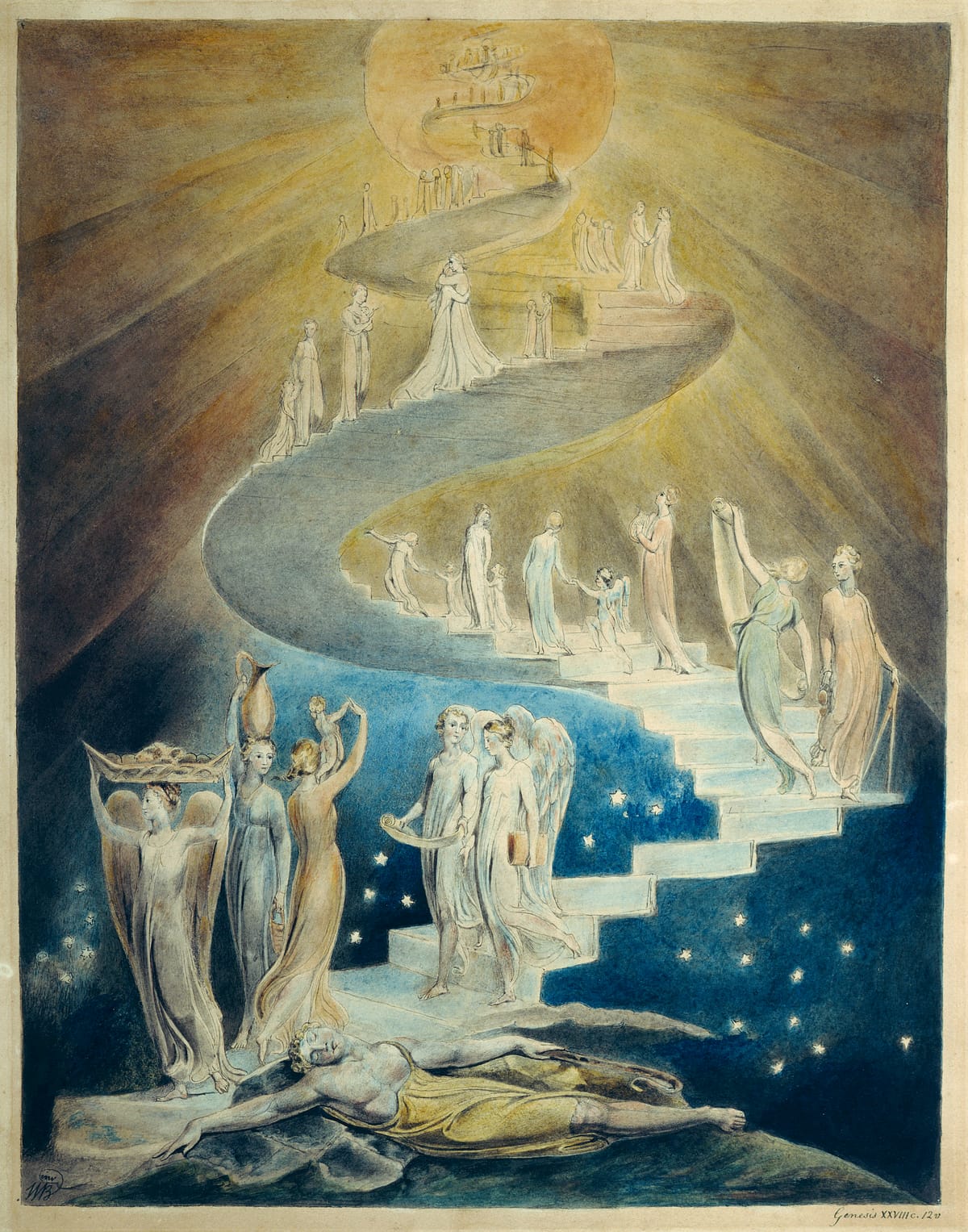

Yakov awakes from his dream afraid. He vows that if Hashem fulfills His promises, Yakov will accept the obligations of being a Jew. He's bargaining with Hashem. What are the promises made to Yakov and us, his descendants? What are the obligations of Jews, agreed/accepted on our behalf by our ancestors?

Sforno, Bereshis 28:20

In short, Yakov asks for the dignity required for spiritual focus: you can't worry about mitsvos when you're hungry or otherwise barely able to survive. And why should we offer devotion to a god who fails to provide for our most basic needs? How can we daven or improve the world or find our avode (purpose) when, as Sforno says, we're forced to violate our own integrity and by extension, Hashem's integrity? As we say in our daily liturgy: "What profit is there in my blood, when I go down to the pit? Shall dust praise You? Shall it declare Your truth?" (Tehillim 30:10).

רש“י, בראשית כח:כ

Rashi, Bereshis 28:20

According to Rashi, the righteous are not forsaken and neither are their children. The implication is: anyone who must beg for bread—who lacks basic human dignities—is not righteous, or at least not of righteous yikhus (heritage). The children are punished for the sins of their parents. This is fundamentally unjust. If Rashi is correct, then it is Hashem's righteousness which is called into question, not that of starving people.

Earlier in this parsha Hashem said, "And behold, I am with you" (Bereshis 28:15). But Yakov doubts this when he says "If G-d will be with me". Rabbi Huna said in the name of Rabbi Acha, "from here you infer that there is no assurance [even] to the righteous in this world." (Bereshis Raba 76:2). Contrary to Rashi, they say that the righteous too can starve.

This is the end of the public preview for four weeks. Sign up for $5 a month to read the full dvar.

Money shouldn't a barrier to accessing writing, art, and culture. If $5 a month isn't sustainable for you, please email me and I'll send you the link to sign up for free.

But if you can afford it, please consider signing up. This newsletter helps sustain my unpaid community work as a Jewish lay-leader and food distributor.

Whether righteous or not, the forsaken—the hungry—are not bound to the same obligations as those of us who are given our bread, our clothing, and our peace. If we are afforded what we need, we are expected to attain higher spiritual goals than simply survival.

Rambam and Da'at Zekanim argue that Yakov is not offering conditional servitude, but rather an unconditional vow. Sforno elaborates:

ספֿורנו, בראשית כח:כא

Sforno, Bereshis 28:21

We are supposed to act as though we are completely assured that Hashem will not forsake us, and that we will be judged if our devotion—to our spiritual work, whatever that may be—is lacking. This vow was made by Yakov on behalf of all Jews who come after him. But what of the forsaken: those who already have this counter-assurance which robs their dignity and prevents them from doing anything other than survive?

חזקוני, בראשית כ:כח

Khizkuni, Bereshis 28:20

Who is making vows? Those in desperate circumstances. What situation is more dire than living in Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps in flooded tents, denied food fuel medicine and basic dignity by an occupying army? It is precisely the forsaken who make such vows, though it is the forsaken who are exempt from spiritual obligations.

Bread, clothing, and peace. “This is what the righteous ask of G’d. They are only allowed to pray for necessities, the definition being things which a human being cannot do without." (Rabbeynu Bahya 28:20) We should all be aspirationally righteous. We should only be asking Hashem for our bare necessities, especially while the necessities of others are not yet met.

Furthermore, we should only be asking for that which we have already done everything in our power to change. We should be focusing our energy on ensuring that everyone has their basic needs met before asking Hashem for even that, let alone asking for our less urgent needs and desires.

What counts as an urgent, life-saving need?

As we come marching, marching, in the beauty of the day,

A million darkened kitchens, a thousand mill-lofts gray

Are touched with all the radiance that a sudden sun discloses,

For the people hear us singing, "Bread and Roses, Bread and Roses."

As we come marching, marching, we battle, too, for men—

For they are women's children and we mother them again.

Our days shall not be sweated from birth until life closes—

Hearts starve as well as bodies: Give us Bread, but give us Roses.

As we come marching, marching, unnumbered women dead

Go crying through our singing their ancient song of Bread;

Small art and love and beauty their trudging spirits knew—

Yes, it is Bread we fight for—but we fight for Roses, too.

As we come marching, marching, we bring the Greater Days—

The rising of the women means the rising of the race.

No more the drudge and idler—ten that toil where one reposes—

But a sharing of life's glories: Bread and Roses, Bread and Roses.

—"Bread And Roses" by James Oppenheim, written in solidarity with the women's suffrage movement 1911

I am wrestling with the tension between "bread for everyone first" and "bread and roses for all now". I've parred down my lifestyle so that I can give more tsedoke—more money—to people starving in Palestine. Every time I consider buying something nice—something not strictly necessary—for my friends or myself, I'm overcome with anxiety and doubt. Yes, I believe that we not only deserve but require bread and roses: basic necessities and art, beauty, luxury, the dignity to not just survive but thrive and enjoy the world. But I need roses less than my comrades in Gaza need bread.

Of course, this is an individualist view of resource scarcity—it's not systemic, and it's probably not helpful. However, I've been in poverty before. I know that $50 can be literally life-saving, and it's impossible for me to justify spending it on something like concert tickets or getting my shoes repaired when my friends in Gaza haven't eaten in eight days.

But I also know the importance of art: when I was hungry, it gave me a reason to keep living. Still, I keep coming back to the harsh reality that if you give a starving person money, they will spend it on something they need—food, housing, medicine, maybe drugs—not a luxury item. And if anyone needs roses right now, it's not me, it's Palestine.

I have spent so much time thinking about what it was like to be in the ghettos and camps of Eastern Europe. But before October 7 I didn't think before about what it was like to be someone living abroad, trying to help from across an ocean in a country actively funding the atrocities. The majority of people didn't (and today, don't) do anything and I was angry at them when I read about the war. But now I am them, and I'm trying to figure out how to be effective for my comrades here and in Palestine. I can stomach being less comfortable during wartime in order that it saves lives. It's easy to get overwhelmed and disassociate, and I have many times in the last year. What I've settled on is: I give money as much as I can so they can have bread, and I write here and do other cultural work (which doesn't direct funds away from Palestine) so we can all have roses. Of course, I also adhere to the BDS boycott list and strongly encourage you to as well.

I'm sure my reasoning is imperfect and my tactics could be improved; I welcome your thoughts, comrades. But if I know anything, it's that while anyone, any one person, is forsaken, it is an affront to our collective dignity. Even as Hashem forsakes us, we cannot forsake each other.