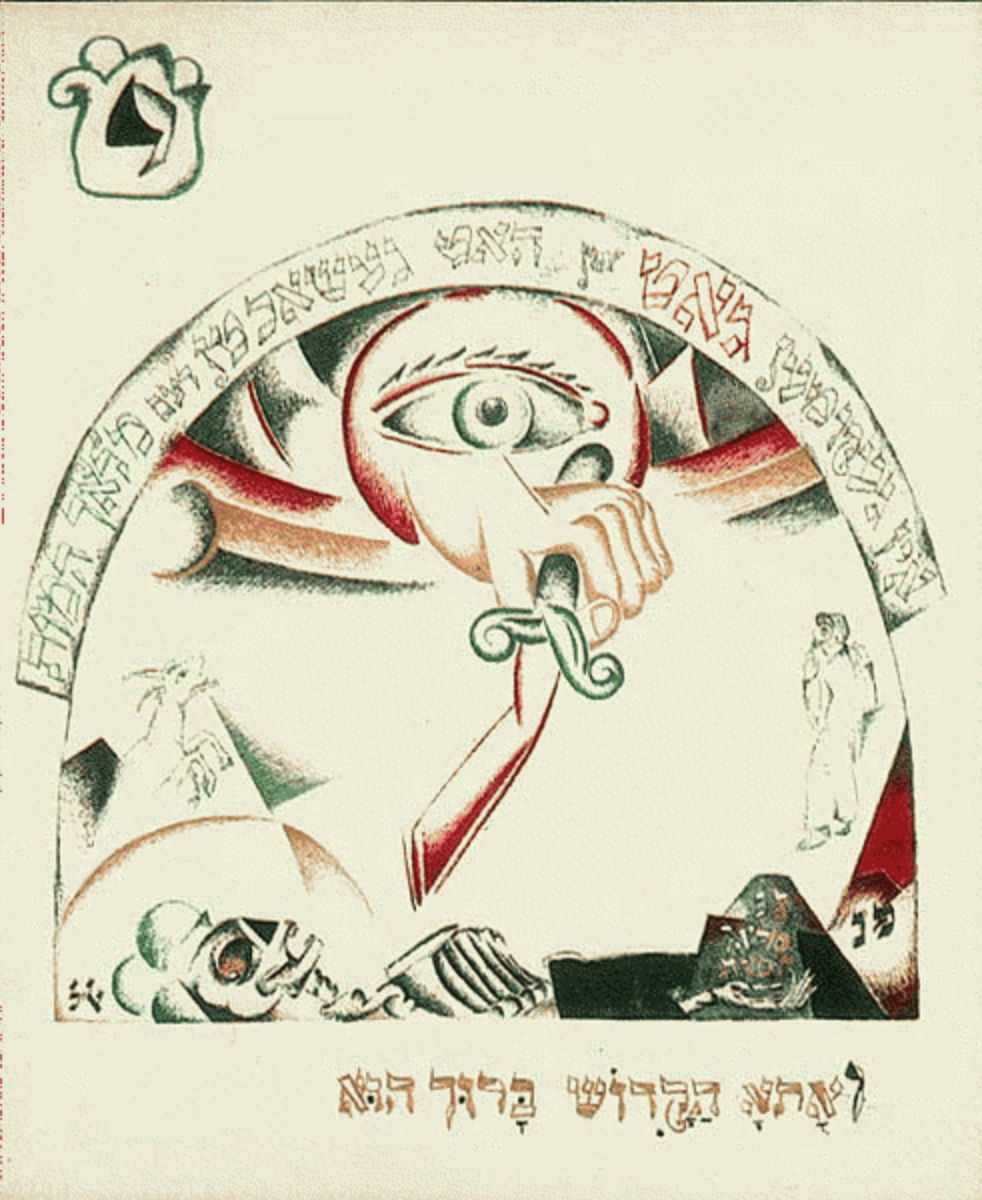

Voeyro / וארא

This is a weekly series of frum, trans, anarchist parsha dvarim. It's crucial in these times that we resist the narrative that Zionism owns or, worse, is Judaism. Our texts are rich—sometimes opaque, but absolutely teeming with wisdom and fierce debate. It's the work of each generation to extricate meaning from our cultural and religious inheritance. I aim to offer comment which is true to the source material (i.e. doesn't invert or invent meaning to make it more comfortable) and uses Torah like a light to reflect on our modern times.

Content note: Genocide in Gaza

An appeal: My friend Areej and her family have finally been allowed to return home in Central Gaza after living in an IDP camp tent for months, but their house was partially destroyed by the bombing. If you can donate even $5, please do. May this be the start of a lasting and meaningful peace as we all rebuild and move toward a free Palestine.

The parsha opens with Hashem speaking to Moishe Rebeynu. He reiterates that he has now heard the cry of the Israelites and remembers the covenant (this only-just-now hearing and remembering was the subject of my dvar for parsha Shemoys last week). It goes on to narrate suffering and collective punishment and the exceptional Jewish relationship to God: the tension between oneness and collectivity vs. separation and specialness.

The ceasefire has taken effect. There is finally something like relief after nearly 15 months of mass death. Has the cry of the people finally been heard? Why did it take so long?

Shemoys 7:3

Moishe and Aaron perform minor miracles with their rods to prove the existence of God. This does not sufficiently move Paroy to release the Israelites, because Hashem has hardened Paroy's heart.

Why does Hashem harden Paroy's heart? Rashi says it is so Hashem has good cause to prove Himself not to Paroy and the heathens of Mitsrayim but to the Israelites. All of the suffering and death that will result from the plagues are in service of strengthening the relationship between Hashem and the soon-to-be Jews.

וְאוּלָם בַּעֲבוּר זֹאת הֶעֱמַדְתִּיךָ בַּעֲבוּר הַרְאֹתְךָ אֶת־כֹּחִי וּלְמַעַן סַפֵּר שְׁמִי בְּכׇל־הָאָרֶץ׃

Shemoys 9:15–16

But the text later states that the purpose of these horrible miracles is not only to secure the faith of the Israelites. Hashem wants attention, recognition, and worship or at least respect and reputation throughout not only Mitsrayim but the whole world. This divine outburst does not seem to come from a place of strength. What kind of relationship is Hashem cultivating with the Jews that requires violence not only toward those who oppress us, but innocents who happen to live there too? Why is collective punishment the answer?

The first seven plagues are: the Nile turning to blood; frogs; lice; swarms of insects; pestilence of beasts; boils; and heavy hail.

During the plague of frogs, Paroy asks Moishe for relief; he says he will let the people go if the frogs stop. Moishe pleads with Hashem to stop the plague; Hashem does as Moishe asked and kills all the frogs, and the people of Mitsrayim pile up the dead frogs (or, as some read it, one single giant frog) "until the land stank". When Paroy sees this relief, his heart is once again hardened and he is too stubborn to let the people go, so Hashem brings the plague of lice. The same thing happens during the plagues of swarming insects and heavy hail: Paroy promises to release the Israelites if the plagues stop, but once they stop, he goes back on his word and Hashem brings a new plague.

The Israelites are not directly affected by the plagues; only the Mitsrayim are. We are to conclude that (despite historical evidence to the contrary) the Jews are and will always be safe because we have a special relationship with God.

Shemoys 8:19

The meaning of the word פּדת is uncertain: this translation opts for "distinction", but it could also be division or deliverance. There is a tension in our tradition between recognizing our unique culture and history and obligations as Jews and separating ourselves; and the alleged oneness of humanity, of all that is Hashem which is all that is. There is power in naming difference—challenging the "normalcy" of the hegemonic groups by using words like cis and goy instead of not-trans and non-Jew. This power is neutered by so-called "blindness", flattening, and pretending that everyone is the same. We are different, and according to our texts, only some of us will be redeemed.

During the Pesach seder we hold this tension by both celebrating our deliverance, and diminishing our joy for the suffering caused to the people of Mitsrayim during the plagues by flicking one drop of wine for each plague on our plate. We sympathize for a solemn moment, but we do not go so far as to empathize and recognize their suffering as our own. It's sad that the innocents of Mitsrayim were killed so that we might be free, we might say. But how free are we as a people whose liberation is contingent on the blood of children?

Hashem's violent inaction and subsequent violent actions are incomprehensible, then and now. Moishe Rebeynu pleads for the plagues to stop, and Hashem listens. But it is not enough because each time, Paroy's heart is hardened by God so that a new plague will replace the old.