Yisroy & Tu B'Shvat / יתרו & דער חמישה־עשׂר

This is a weekly series of parsha dvarim written by a frum, atheist, transsexual anarchist. It's crucial in these times that we resist the narrative that Zionism owns or, worse, is Judaism. Our texts are rich—sometimes opaque, but absolutely teeming with wisdom and fierce debate. It's the work of each generation to extricate meaning from our cultural and religious inheritance. I aim to offer comment which is true to the source material (i.e. doesn't invert or invent meaning to make us more comfortable) and uses Torah like a light to reflect on our modern times.

Content note: fascism, abusive power dynamics (both in abstract)

Following the advice of my good friend Lipe following their friend Natalie, I study Torah three times: as though it is literal historical fact; as though it is entirely metaphorical; and as a dialectic between these two positions, both of them true.

This is a parsha about binaries: leaders/followers, authority/subservience, consent/coercion. Binaries lend themselves nicely to dialectics. I also believe this week is also about the impossible, and the morally-necessary, and how those are often the same thing.

Shemoys 18:14

"The thing you are doing is not right; you will surely wear yourself out, and these people as well. For the task is too heavy for you; you cannot do it alone."

Shemoys 18:17–18

It opens with Moishe Rebeynu's father-in-law advising him to delegate. It's a short lesson on effective leadership and avoiding burnout, and an evergreen reminder: it is neither possible nor desirable for one person to do it all.

Moishe appoints "heads" of the people from among the chiefs. As an anarchist I don't love that the solution is hierarchical, but I think we can all take the lesson about collaboration and shared (if uneven) responsibility.

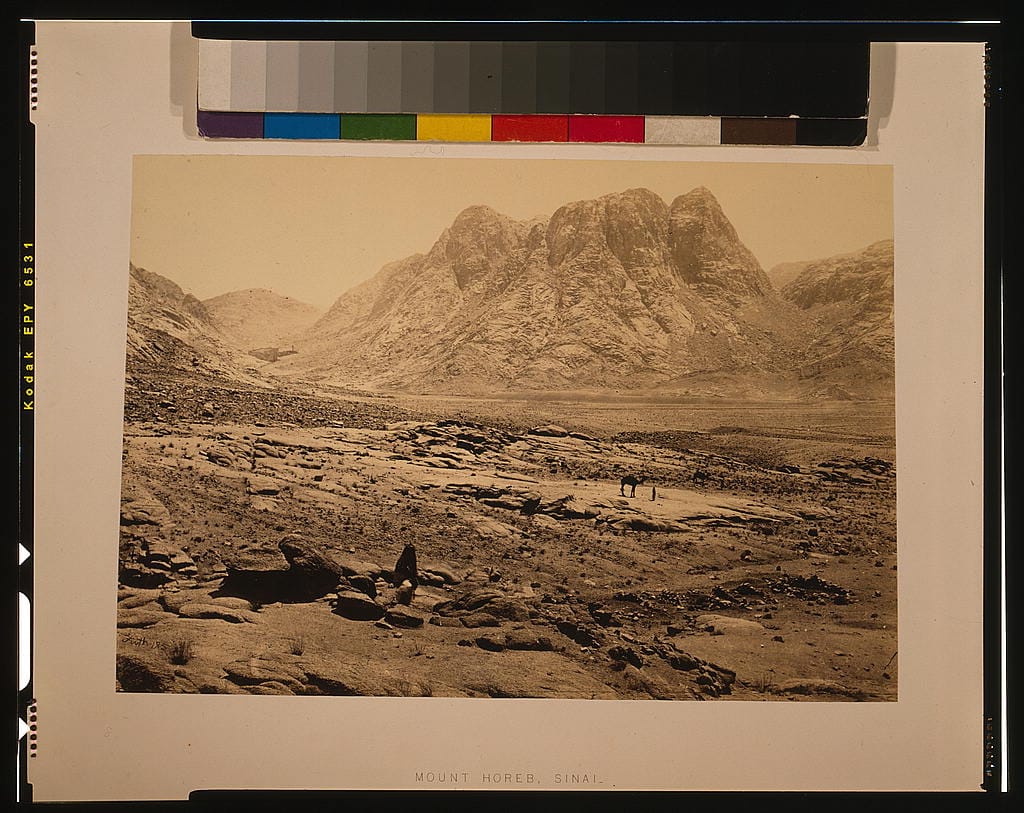

Shemoys 19:18

The mountain—smoking like a kiln while "the horn" blared louder and louder—is terrifying. These are the conditions under which the Israelites accept the Torah, its mitzvos, and the sovereignty of heaven: under duress. We have just seen what plagues Hashem can deliver to those whose hearts are hardened against Him, and in case you forgot (because it's been 40 years now between this parsha and the last), He's here to remind you that His power is infinite. He can and will intervene in the material world to help us and to scare us. Listen to me, lest you die. It's an abusive relationship.

The people ask Moishe to intercede, that they may not hear Hashem's voice. Why? They are not insolent; they're afraid of hearing Hashem's voice, afraid of the sound hitting their ears alongside the horn (which I imagine plays a Shepard Tone). The Divine poses an existential threat. The people want someone else to lead them, to hear and relay instructions, to plead with Hashem on our behalf. If you have faith that G-d is real—and as a witness at Sinai, how could you not—then there is nothing to do but obey completely. But the stakes are high. I understand the urge to absolve ourselves of responsibility, of confrontation, of risk. So it's agreed: Moishe will liaise.

But Moishe is dead. Where is Hashem now? Some of my friends and Rabbis tell me they feel divinity in this world and I'm envious. Has our ancestors' request/cowardice/aversion robbed us (or maybe just me?) of a more direct relationship with G-d? Are most of us simply not strong enough to handle contact with the divine? Even Moishe was not allowed to see Hashem's face, but only permitted to hear Hashem's voice.

In times of fascism, it is impossible for us (or, again, maybe just for me) to talk to G-d right now. Therefore we must. Before gifting/forcing Torah upon us, Hashem gives Moishe a redundant instruction, and Moishe talks back. When G-d says or does something wrong it is our burden and privilege to speak up and demand better. So too must we speak up in the material world. Maybe this is the same thing.

Two poems from The War about fascism and trees, for Tu B'Shvat:

Was sind das für Zeiten, wo

Ein Gespräch über Bäume fast ein Verbrechen ist

Weil es ein Schweigen über so viele Untaten einschließt!

—Bertolt Brecht, Auszug aus "An Die Nachgeborenen", Paris, Juni 15, 1939.

What kind of times are these, where

talking about trees is almost a crime

because it implies silence about so many horrors!

— Bertolt Brecht, excerpt from "To Those Born After", Paris, June 15, 1939 (translation mine).

און דאך איז עס שיין, ווי א נס ,

אט דאס ראזעווע צווייגעלע בעז...

אפילו אין אונזערע טעג

פון ביזער דערוואַרטונג און שרעק.

אפילו ביי אונז אויף דער גאס,

ווען ס'גרויסט זיך מיט חוצפּה דער האַס...

עס ציט זיך דאס שווייגעלע בעז

צו דיר און צו מיר, ווי אַ נס...

—„ווי אַ נס“ פֿון זוסמאַן סעגאַלאָוויטש, פֿונעם וואַרשעווע געטאָ רינגלבלום אַרכיוו

And still it is beautiful, like a miracle,

This rosy lilac sprig...

Even in our days

Of evil dread and terror.

Even to us in the street

When hate swells with khutspah...

The little lilac sprig reaches out

To you and to me, like a miracle...

— "Like A Miracle" by Zusman Segalovitch, from the Warsaw Ghetto Ringelblum Archives (translation mine)

Brecht was a goyisher German antifascist and Segalovitch was Jew born in Poland when Poland was Russia. Both poets know that we cannot talk about trees and therefore we must.

May our art and other resistances blossom.