(Trans) Gender Matters: trans theory and international relations

An essay for my MSc; edited in 2025 for clarity

Introduction

This paper identifies the intersections between trans theory and international relations (IR) theory by exposing the international relation’s blindness to gender diversity, and demonstrating the usefulness of trans theory in filling the resulting gaps. Trans theory offers insights and analytical tools which, if employed, would be valuable to international relations as a discipline.

Trans Theory and International Relations

International relations theory is, in short, a theory of the international. Traditionally this involves theories of the state and security, analyzing the relationships and power dynamics among actors (i.e. the state) on the international stage. This “mainstream” IR theory is positivist/rationalist, Anglo-American, and allegedly gender-neutral; structural realism and neoliberal institutionalism are the most prominent mainstream IR theories. Less pervasive are constructivism and the English school, and “critical” IR theories which includes poststructuralism(1), Marxism/neo-Gramscianism, postcolonialism, and of course feminism; they are so named “critical” because they criticize the dominant realist and liberal perspectives, and differ from the mainstream theories in their foundational epistemological and ontological claims.

Outside of feminist work, international relations is blind to gender diversity. This weakens IR as a discipline because recognizing gender diversity offers insight to international politics, as will be outlined below.

Just as it was imperative to include feminism in IR to understand the sexist underpinnings of global politics and the discipline itself, trans theory exposes the ubiquitous cissexism in international relations (the subject) and IR theory (the discipline). Until cissexism in IR is addressed, cisgender heterosexuals will retain the privileged position of perceived “normality”, while trans people will remain “abnormal” and othered. Gender studies has done much to highlight cissexism in its scholarship, and IR has been slow to progress. International relations should be a dialogue “of, about, and for difference”(2), rather than obscuring the diversity of the actors whose behavior and interaction it seeks to explain.

IR is the study of gendered individuals and actors, by gendered individuals. IR is also the study of power relations, and power relations between a plurality of genders are relevant. “Trans theory suggests the importance of power dynamics between things understood as queer and things understood as straight, and between things understood as trans and things naturalized as cis.” (3)

Trans theory, much like feminism, is not a single perspective or united position. Rather, trans theory is “a diverse, vibrant, and contested collection of theories which share an interest in the existence, meaning, and signification of the trans in political and social life” (4). Including trans theory in IR is not just merely highlighting the plight of yet another marginalized group, though such an effort should be seen as worthy for its own sake; rather trans theory has much to offer international relations theory relating to issues of identity, plurality, and remaining inquisitive in the face of the discipline’s own assumptions.

Due to the scope of this essay, the focus will be on trans theory and will not include comments on queer theory, though these fields are closely related. Queer theory includes both queer readings of texts and theories on “queerness”, expanding on gay/lesbian theories which inquired into the “naturalness” of homosexual behavior. It includes all sexual and gender identities which are seen as nonconforming or deviant. “Queerness” could be argued to be ultimately post-gender, unconcerned with the binaries of male/female and hetero/homo. Trans theory examines the liminality between genders, but uses “male” and “female” as reference points.

Vocabulary

“Sex” is the perceived biological “maleness” or “femaleness” of a body, relating to that body’s sex organs. The binary of “male” and “female” is problematic because it does not allow space for anything separate or in between these two distinctions. Sex is argued by feminists to be a social construction, or a performance, but others continue to discuss sex as a biological fact.(5)

Feminism defines “gender” as a social and culturally constructed concept which characterizes people as “men” and “women”, and “masculine” and “feminine”, based on their perceived sex. Infants are assigned a gender at birth which “matches” their sex. Gender identity is the experienced gender of an individual, which may or may not match their assigned gender at birth. Gender expression is the gender people choose to present themselves as, which can be separate from their gender identity and/or the gender they were assigned at birth. The gender binary is the dichotomous concept of only two genders: men and women. This binary, like the male/female sex binary, is destructive because it provides only two options for defining one’s gender, while many people’s lived experiences include fluid, transitory, oscillating, or simply nontraditional gender(s); the gender binary also dictates that men are expected to be strictly masculine, and women are expected to be strictly feminine.

Sexual preference refers to whom one finds sexually and romantically attractive. Heterosexuals are attracted to “the other” sex; homosexuals are attracted to “the same” sex; bisexuals are attracted to both “the other” and “the same” sexes; pansexuals are attracted to multiple or all sexes; and asexuals are not attracted to any sex. Heteronormativity is the assumption of the normalcy of heterosexuality, while other sexualities (homo-, bi-, a-, and pan- to name a few) are viewed as abnormal. Heterosexism is the discrimination against people who are not heterosexual: heterosexism can exist in the form of harassment and abuse, or less explicitly through the propagation of heteronormative language and cultural attitudes.

“Trans” is a prefix referring to people who do not identify as (solely) the gender or sex they were assigned at birth, or people who do not conform to societal gender norms.(6) Transgender is a broad term referring to people who transgress traditional gender norms. Transsexual is a more specific term referring to people who have adapted their gender role(s) and/or bodies to be congruent with their gender identity: this may include cross-living (cross-dressing all of the time), hormone therapy, surgery, or other body modifications. MtF is the abbreviation for “male to female”, people who formerly identified as male or were deemed male at birth who now identify as female; FtM for “female to male” for those who formerly identified/were identified by others as female who now identify as male. Transitioning is the process trans people begin when they start living as their gender, which may involve “coming out”, learning to change their gender expression, hormone treatment, or body modifications. Gender dysphoria is the psychological discomfort with one’s own body and/or gender assignment, and the resulting cultural gender expectations. Gender dysphoria is also a clinical psychiatric diagnosis to be included in the DSM-5, which is seen as stigmatizing and offensive to many; yet a positive diagnosis is often required to receive insurance coverage for sex-reassignment/gender-affirming therapy or surgery.(7) Transphobia is the fear of or discrimination against trans or gender-variant people: trans people statistically experience high levels of abuse and harassment, and are disproportionately raped and murdered.

“Cis” is the prefix given as the opposite of “trans”. Cisgendered peoples’ gender identity matches their assigned gender. Cissexism is the preference toward cisgendered people, and the discrimination against and othering of trans and gender-variant people. The prefix “cis” and its associated terms are designed to challenge the normalcy of cisness and the abnormality of transness.

“Queer” is an umbrella term used to describe people whose sex, sexual preference(s), and/or gender identity is nonconforming. There is some controversy surrounding “queer” because it was used as a derogatory slur against men perceived to be gay and/or effeminate in the late 19th and 20th centuries, but the term has since been reclaimed in the 1990s by activists and allies as a positive self-identifier; some LGBT people avoid it because of its hate-speech origins, and its association with radical politics or the younger generation. Genderqueer people may or may not be trans, and identify their gender to be outside of traditional norms.

Trans Theory and Feminism

“The personal is international.”(8) Feminist scholarship in IR, while diverse, makes two consistent claims: first, that gendered relations of power work to the advantage of men and reinforce hierarchies of power between men and women (and between races, classes, and nations) which affect and are affected by international politics; and second, that dominant approaches to studying international politics (e.g. neorealism and neoliberalism) reflect gendered assumptions of the world. Heyes writes, “Feminists of all stripes share the political goal of weakening the grip of oppressive sex and gender dimorphisms ... with their concomitant devaluing of the lesser terms female and feminine.” Trans theorizing can further this agenda with work which likewise disrupts sexist assumptions but also highlights cissexism, further breaking down gender binaries and the normative linkages many people assume to exist between (perceived) biological sex and the social roles and statuses that a particular form of body is expected to occupy.

Feminism and trans theory share a common methodology: first-level analysis and critical discussions based on the “lived experiences” of individuals. This is contrary to the “scientific” methodology of postwar mainstream IR, modeled after the natural sciences as a response to ideological fascism.

Feminism has done much to expose gender-blindness in IR and IR theory, but is itself often blind to gender diversity and the diversity of sexed bodies. Feminist work looks for the men and women, the masculine and feminine, and the masculinized and feminized, and for the instances when these boundaries are artificial or when liminal space between the binaries is important. Trans theory shares these objectives and can aid in breaking not only the gender binary, but the sex binary as well.

Feminist politics are too often reduced to “women’s issues”. As Tickner reminds us:

[G]ender is not just about women; it is also about men and masculinity, a point that needs to be emphasized if scholars of international relations are to better understand why feminists claim that it is relevant to their discipline and why they believe that a gendered analysis of its basic assumptions and concepts can yield fruitful results.

This is not to suggest a shift to so-called “masculinity studies”; rather, using a trans perspective could aid in broadening feminism to account for gender diversity, potentially enhancing IR’s understanding of other (perceived) dichotomies and (actual) pluralities.

The fundamental contradiction between feminist theories and trans theories are their understanding of gender: feminists view gender as performative, socially constructed, and largely related to the power dynamics between the masculine and the feminine; trans theorists see gender to be socially constructed and primordial, in combination. Likewise, some feminists see sex as biological and dichotomous, while trans theory shows sex to be malleable, fluid, and multiple. The relationship between trans theory and feminism is strained because the suggestion that not only sex but gender is (partially) prior to social construction threatens feminism’s project to deconstruct gender dichotomies: the very existence of trans people reveals the false nature of sex and gender binaries. Still, the feminist project and trans theory both attempt to dissect gender hierarchies and include gender variance (e.g. things other than maleness) in political discussions.

Trans theory could also have links with other IR theories. Like most critical theories, trans theory is post-positivist. Trans theory, Marxism, and postcolonialism share the aim of deconstructing power hierarchies around understanding the influence that those power relations have on the discipline. IR would benefit from exploring these and other yet unexamined similarities.

Identity: Self vs. Other

Identity politics are highly relevant to IR. Huntington and Fukuyama suggest cultural identity is a major fault line of international relations. In a discipline which studies and compares actors on a global scale, grouping them based on (perceived) identifying factors, the use of identity in IR is worth examining.

International relations is overwhelmingly dominated by privileged, white, Anglo-American male voices, discussing a world which contains a multitude of diverse identities and yet others marginal groups: Orientalist perspectives of “the East”; masculine approaches to gender and women; and cissexist approaches to gender and sex.

Trans theory writes identity as non-static.

Many trans people see their gender identity as primordial/fixed, while their sex identity needs to be changed to reach accord with their gender identity. Others see their sex identity as primordial/fixed but not represented in their physical being. Still others see their sex identity and their gender identity as both fluid and flexible. (9)

IR theory views identity as fixed: Self and Other. Facets of identity are assumed to be ontological facts, such as ethnic membership or nationality. This rigid understanding of identity does not reflect the reality of a complex global system where people cross not only borders but religions, castes, and genders. Trans theorizing offers IR the tools to understand “crossing” as a process. Likewise, trans theory can help us understand the nature of “passing”(10) after crossing:

Thinking about “passing” while crossing or once crossed might help us understand how to identity and deal with the unseen in global politics. For example, spies rely on “crossing” national and/or ethnic groups as a member of the group they are charged with getting to know. Many military maneuvers are built on “crossing” into enemy social and political life and “passing” either as local or as part of the surrounding landscape.(11)

This forces us to consider: the implications of the ability to pass for the stability of categories taken for granted in IR; when and why people disidentify with their assigned or primordial states; and when and why people are disidentified from their primordial groups by those within the group. These debates could aid IR in understanding identity politics and cultural violence.

The narrative surrounding trans people suggests that gender is signified by genitalia: “a man trapped inside a woman’s body” (or vice-versa); male cross-dressers and transvestites have upheld that their maleness/masculinity had a feminine side, rather than challenge the construction of their gender roles.(12) Transphobic rhetoric suggests that genitals are the essential determinants of sex. Bettcher elaborates:

For example, an MTF who is taken to misalign gender presentation with the sexed body can be regarded as “really a boy,” appearances notwithstanding. Here, we see identity enforcement embedded within a context of possible deception, revelation, and disclosure. In this framework, gender presentation (attire, in particular) constitutes a gendered appearance, whereas the sexed body constitutes the hidden, sexual reality.

This narrative suggests that it is less confrontational to transform the physical body than to shift the social understanding of the body. Since the physical body and its biological sex are therefore not essential to the Self, there is little room for other identifiers to make claims of ontological stability: it is possible to individuals to dis- and re-identify themselves. Building on the feminist aim and approach of reconciliation of the Self and Other, strategic disidentification could be a useful tool in conflict resolution where parties seem diametrically opposed.

Transness illuminates a ‘category crisis’ where the boundaries between genders are not only blurring and being crossed, but they are imagined in the first place.(13) Perhaps other boundaries and identifiers assumed to be prior in international politics require further investigation.

Visibility

Trans people are both invisible and unheard in the halls of power, and hyper-visible, our bodies the object of gaze and fascination. Sjoberg and Shepherd suggest that the invisibility of genderqueer and trans bodies in security studies is not a function of representational practice but of cis privilege, citing several examples of gender fluidity in war and high politics.

“Coming out” is one way of declaring visibility, despite the social and legal difficulties for trans people. Yet, Butler asks, “for whom is outness a historically available and affordable option? Is there an unmarked class character to the term, and who is excluded?” Outness presumes visibility and the ability to be heard. Outness also assumes a “true self” which is contrary to appearances, and an opposite “in-ness” which is dishonest or misrepresentative; IR could benefit from not only discussing actors in terms of their visibility, but also the difference between the outside perception of them and their self-perception. The difference between group and individual visibility is also noteworthy: “(in)visibility can be addressed according to the lived experience of people involved or through cultural representations ... which universalize the opinions of some while excluding those of others.”(14) This highlights power dynamics between group and individual voices, and of self-reinforcing marginality. Which identities are more or less legitimate than others by definition? How does being trapped in, or out, of the public gaze affect groups and individuals at the margins of politics? Is it possible to be both in and out of the public gaze simultaneously?

The hyper-visibility of trans people in the public gaze is similar to that of Orientalism. Saïd characterized Orientalism as the result of fractious circumstances, or a power/vocal asymmetry. Both “the Orient” and trans people are seen by the public to be “exotic”, “sensual/sexual”, and “weak” and in need of rescuing. This visibility of trans bodies is, in IR debates, a form of discursive violence.

Seeing cisgender privilege may allow us to recognize other forms of privilege in the theory and practice of global politics that are assumed to be so normal they have become invisible; what other political, social, or cultural attributes are so normalized that their alternatives are oppressed or silenced?

Security

Security has always been central to international relations theory. Realists have defined security in political and military terms referring to the integrity and protection of state territory; neo/structural realists focus on an anarchic international system. Feminists write security as all forms of violence, which exists on multiple levels, including physical, structural, and ecological. Like feminism, trans theory begins with the individual as the level of analysis in security because gender (diversity) is marginal to the power structures of states. Both theories also question the role of the state as a provider of security, because the state is both disengaged from the private sphere of social relations, and because the state itself reinforces gendered power dynamics at the expense of women and gender-variant individuals.

Sjoberg uses the example of Pfc. Chelsea Manning, whose lawyers heavily implied that her gender identity disorder caused her such distress that she could not be expected to make reasonable decisions at the time of her alleged leaking of classified materials to Wiki Leaks, to illustrate that “gender conformity relates discursively and politically to safety while gender ambiguity is related to danger”.

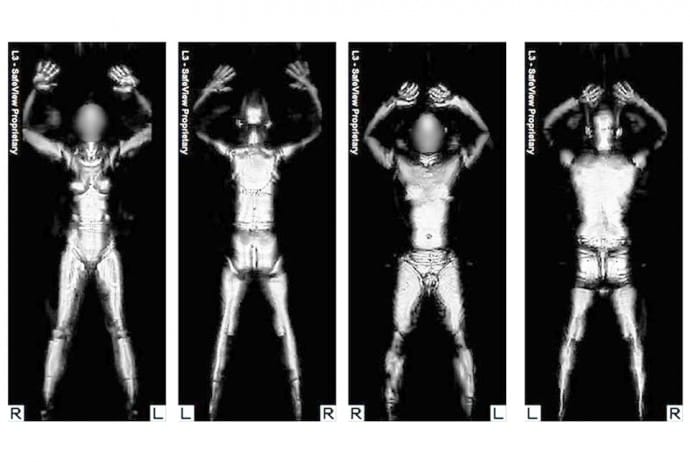

This point is further made by Sjoberg and Shepherd regarding Whole Body Imaging (WBI) scanners at airports as a counterterrorism measure: not only do the scanners potentially violate religious commitments to modesty and child pornography laws, but they subject trans people to increased harassment and suspicion. An American DHS Advisory to security personnel claims: “Terrorists will employ novel methods to artfully conceal suicide devices. Male bombers may dress as females in order to discourage scrutiny”. This equates gender variance as threatening and potentially being predisposed to violence.

Conclusion

The intersection between trans theory and IR theory is under-examined and has the potential to further not only the feminist project, but to contribute to more mainstream debates in the discipline. To expel oppressive assumptions from academic discourse we should not simply to engage with trans theory, but employ an intersectional approach to oppression, broadening our view to include multiplicities of oppressed peoples; too often individuals oppressed by gendered hierarchies are those also oppressed by class and/or racial power relations. Cross-discipline research and dialogue between different theories in international relations could foster positive change in the discourse of power.

Footnotes

- Richard Ashley & R. B. J. Walker, eds. “Speaking the Language of Exile”. International Studies Quarterly 34(3) (1990).

- Naeem Inayatullah & David L. Blaney. International Relations and the Problem of Difference (Global Horizons). New York: Routledge, 2004, p 219.

- Sjoberg, “Toward Transgendering International Relations?”, International Political Sociology 6 (2012): 337–354, p 341.

- Ibid, p 338.

- For more on non-binary biological sex, see: Jane Seymour, “Hermaphrodite”, The Lancet 377(9765) (2011): 547; Emily Grabham, “Citizen Bodies, Intersex Citizenship”, Sexualities 10(1) (2007): 29–48.

- For the purposes of this essay, “trans” is preferred to “transgender”, “transsexual” and others because it allows for more variance as a self-descriptor. However, it should be noted that some believe its broadness to oblique these variances and force all non- gender conforming people into a single group, erasing in-category differences. It is also preferred to “trans-” and “trans*” because more clearly describes identity in the same way as race or sexual orientation. As one trans man explains, “if you write about trans men, we tend to use two words for it now, because transmen is weird—nobody says blackmen or gaymen. Makes us seem like some kind of creature that’s not really a man, like merman.”

- American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5), May 18, 2005.

- Cynthia Enloe, Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics (2nd ed.) London and Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000, p 195.

- Sjoberg, “Toward Transgendering International Relations?”, pp 349–350.

- For trans people, “passing” is the ability for a person to convincingly present themselves in another gender than which they live full-time or where assigned at birth. The term is used both to indicate a lifestyle (no one knows that the person is trans) and an event (the person passed at a party last night).

- Sjoberg, “Toward Transgendering International Relations?”, p 348.

- Whittle, “Gender Fucking or Fucking Gender?”, p 118.

- Ibid, p 119.

- Alumie Moreno, “Open Space: The Politics of Visibility and the Gltttbi Movement in Argentina”. Feminist Review 89 (2008): 138–143, p 140–141.

Bibliography

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel of Mental Disorders (4th ed., Text Revision; DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: 2000.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manuel of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM-5). May 18, 2013.

Ashley, R. & Walker, R. B. J. eds. “Speaking the Language of Exile”. International Studies Quarterly 34(3) (1990).

Robert Axelrod & Robert Keohane (1985) “Achieving Cooperation under Anarchy: Strategies and Institutions”, World Politics 38: 226-254.

Balzer, Carsten. “Every 3rd Day the Murder of a Transgendered Person is Reported”. Liminalis 3 (July 2009).

Barkawi, Tarak “Empire and Order in International Relations and Security Studies”. In Bob Denemark (ed.) The International Studies Encyclopedia, New York: Blackwell, 2010.

Beauchamp, Toby. “Artful Concealment and Strategic Visibility: Transgender Bodies and U.S. State Surveillance After 9/11”. Surveillance & Society 6(4) (2009).

Bettcher, Talia M. “Evil Deceivers and Make-Believers: On Transphobic Violence and the Politics of Illusion”. Hypatia 22(3) (2007): 43–65.

Butler, Judith. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Butler, Judith. Undoing Gender. New York: Routledge, 2004

Buzan, Barry. “Culture and International Society”. International Affairs 86(1) (2010): 1-25.

Cox, Robert W. “Gramsci, Hegemony and International Relations: An Essay in Method”. Millennium 12(2) (1983).

Enke, Anne. Transfeminist Perspectives in and beyond Transgender and Gender Studies. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2012.

Enloe, Cynthia. Bananas, Beaches and Bases: Making Feminist Sense of International Politics (2nd ed) London and Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

[European] Commissioner for Human Rights. “Human Rights and Gender Identity”. Issue Paper, Council of Europe, 2009.

Fausto-Sterling, Anne. “Bare Bones of Sex: Part I, Sex and Gender”. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 30(2) (2005): 345–370.

Fukuyama, Francis. “The End of History”. The National Interest (1989).

Grabham, Emily. “Citizen Bodies, Intersex Citizenship”. Sexualities 10(1) (2007): 29–48.

Huntington, Samuel P. Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996.

Heyes, Cressida J. “Feminist Solidarity after Queer Theory: The Case of Transgender”. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 28(4) (2003): 1093–1120.

Inayatullah, Naeem & Blaney, David L. International Relations and the Problem of Difference (Global Horizons). New York: Routledge, 2004.

Jones, Adam. “Does ‘Gender’ Make the World Go Round? Feminist Critiques of International Relations”. Review of International Studies 22 (1996): 405–429.

Lane, Riki. “Trans as Bodily Becoming: Rethinking the Biological as Diversity, Not Dichotomy”. Hypatia 24(3) (2009): 136–157.

Moreno, Alumie. “Open Space: The Politics of Visibility and the Gltttbi Movement in Argentina”. Feminist Review 89 (2008): 138–143.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

Morland, Iain & Willox, Annabelle (ed.s). Queer Theory. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005.

Namaste, Vivianne. “Undoing Theory: The ‘Transgender Question’ and the Epistemic Violence of Anglo-American Feminist Theory”. Hypatia 24(3) (2009): 11–32.

Peterson, V. S. “Sexing Political Identities/Nationalism as Heterosexism”. International Feminist Journal of Politics 1(1) (1999): 34–65.

Roen, Katrina. “‘Either/or’ and ‘Both/Neither’: Discursive Tensions in Transgender Politics”. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 27(2) (2002): 501–522.

Saïd, Edward W. Orientalism. London: Penguin Book Ltd., 2003 [1979].

Scott-Dixon, Krista. “TransForming Politics: Transgendered Activists Break Down Gender Boundaries and Reconfigure Feminist Parameters”. Herizons (January 2006): 21–45.

Seymour, Jane. “Hermaphrodite”. The Lancet 377(9765) (2011): 547.

Shepherd, Laura J. “Gender Matters in International Relations”. e-IR (2010). Accessed 21 April 2013.

Shepherd, Laura J. & Sjoberg, Laura. “Trans Bodies in/of War(s): Cisprivilege and Contemporary Security Strategy”. Feminist Review 101 (2012): 5–23.

Sjoberg, Laura. “Seeing Gender in International Security”. e-IR, 5 June 2012. Accessed 20 April 2013.

Sjoberg, Laura. “Toward Transgendering International Relations?”. International Political Sociology 6 (2012): 337–354.

Stryker, Susan. “(De)Subjugated Knowledges: An Introduction to Transgender Studies”. In The Transgender Studies Reader, ed. Susan Stryker & Stephen Whittle. Los Angeles: CRC Press, 2006.

Tickner, J.A. “You Just Don’t Understand: Troubled Engagements between Feminisms and IR Theorists”. International Studies Quarterly 41(4) (1997): 611–632.

Waltz, Kenneth. “Structural Realism After the Cold War”. International Security 25(1) (2000): 5–41.

Waltz, Kenneth. Theory of International Politics. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1979.

Wendt, Alexander. “Anarchy is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics”. International Organization 46(2) (1992): 391-426.

Whittle, S. “Gender Fucking or Fucking Gender? Current Cultural Contributions to Theories of Gender Blending”. in K. Ekins & D. King (ed.s), “Blending Genders: Social Aspects of Cross-Dressing and Sex Changing”, London, Routledge, 1996.

Wilcox, Lauren. “Gendering the Cult of the Offensive”. Security Studies 18(2) (2009): 214–240.

Winters, Kelley. “Gender Dissonance: Gender Reform and Gender Identity Disorder for Adults”. Journal of Psychology and Human Sexuality 17(3/4) (2006): 71–89.

Winters, Kelley. “GID [Gender Identity Disorder] Reform Weblog”. Last modified 7 December 2012. www.gidreform.wordpress.com.

Wolfers, Arnold. Discord and Collaboration: Essays on International Politics. Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 1962.